-

What happened?

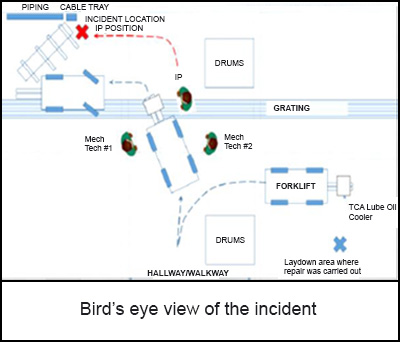

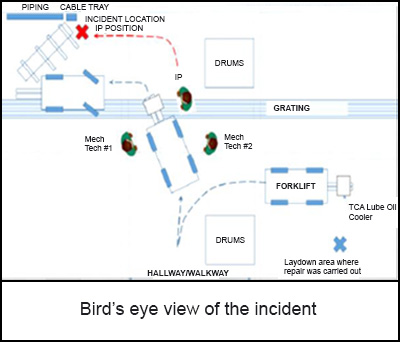

Following repairs, a 1,500kg (3,307lbs) lube oil cooler was planned to be reinstalled.

The work permit (for breaking containment) for cooler reinstallation was not approved because it required improvement, so the marine supervisor in charge of forklift operations assumed the reinstallation wouldn’t go ahead the next day. It was later approved that evening, but the marine supervisor wasn’t informed.

The next day, the maintenance supervisor contacted the forklift operator three times asking the cooler to be moved from the laydown area.

During the lift, three maintenance technicians, who were not associated with the cooler movement, observed an unstable load during transit and attempted to stop the work, which was ignored by the forklift operator.

The technicians followed the cooler as it was being moved, which toppled over and fatally struck one of them.

-

Why did it happen?

The permit was approved after daily operations had ended, therefore it wasn’t discussed during the dayshift’s handover meeting, and the supervisor in charge of lifting operations didn’t know the lift was going to go ahead.

Material movement operations were managed under a separate general permit, allowing activities to go ahead that should really have been managed as a ‘life saving action’.

the job safety analysis was not discussed or followed prior to the movement (load was not secured, no spotter, individuals were in the risk area).

A last-minute risk assessment was not conducted.

The forklift operator’s training dated back to a considerable time in the past, and had demonstrated higher risk tolerance behaviours.

-

What did they learn?

Hazardous work activities (e.g., moving unsecured non-palletised load) should be properly managed and meet work management requirements, including competency verification.

Ensure work team(s) can describe lifting and hoisting requirements and demonstrate use during the task execution.

Ensure workers recognise higher risk tolerance understand when to use “stop work” authority and know that everyone has the authority to exercise it if they perceive a safety hazard.

-

Ask yourself or your crew

What kind of similar miscommunications occur here, if any?

How and when should you use the “stop work” authority?

Why is it important to listen to other people’s concerns, even if they are seemingly exaggerated?

What is the benefit of following procedures in a slow and accurate manner, rather than trying to rush tasks?

What improvements or changes should we make to our procedures, controls/barriers, or the way we work?

Add to homescreen

Content name

Select existing category:

Content name

New collection

Edit collection

What happened?

Following repairs, a 1,500kg (3,307lbs) lube oil cooler was planned to be reinstalled.

The work permit (for breaking containment) for cooler reinstallation was not approved because it required improvement, so the marine supervisor in charge of forklift operations assumed the reinstallation wouldn’t go ahead the next day. It was later approved that evening, but the marine supervisor wasn’t informed.

The next day, the maintenance supervisor contacted the forklift operator three times asking the cooler to be moved from the laydown area.

During the lift, three maintenance technicians, who were not associated with the cooler movement, observed an unstable load during transit and attempted to stop the work, which was ignored by the forklift operator.

The technicians followed the cooler as it was being moved, which toppled over and fatally struck one of them.

Why did it happen?

The permit was approved after daily operations had ended, therefore it wasn’t discussed during the dayshift’s handover meeting, and the supervisor in charge of lifting operations didn’t know the lift was going to go ahead.

Material movement operations were managed under a separate general permit, allowing activities to go ahead that should really have been managed as a ‘life saving action’.

the job safety analysis was not discussed or followed prior to the movement (load was not secured, no spotter, individuals were in the risk area).

A last-minute risk assessment was not conducted.

The forklift operator’s training dated back to a considerable time in the past, and had demonstrated higher risk tolerance behaviours.

What did they learn?

Hazardous work activities (e.g., moving unsecured non-palletised load) should be properly managed and meet work management requirements, including competency verification.

Ensure work team(s) can describe lifting and hoisting requirements and demonstrate use during the task execution.

Ensure workers recognise higher risk tolerance understand when to use “stop work” authority and know that everyone has the authority to exercise it if they perceive a safety hazard.

Ask yourself or your crew

What kind of similar miscommunications occur here, if any?

How and when should you use the “stop work” authority?

Why is it important to listen to other people’s concerns, even if they are seemingly exaggerated?

What is the benefit of following procedures in a slow and accurate manner, rather than trying to rush tasks?

What improvements or changes should we make to our procedures, controls/barriers, or the way we work?

A 1,500kg (3,307 lbs) lube oil cooler was planned to be reinstalled. The technicians followed the cooler as it was being moved, which toppled over and fatally struck one of them.